When Is It Right for Christians to Sue?

1 Corinthians 6, Faith, Business Disputes, and Fiduciary Duty

Proverbs 11:1 states, "The LORD detests dishonest scales, but accurate weights find favour with him,"

I find 1 Corinthians 6 quite challenging. I worked as a civil and commercial litigation solicitor for a number of years and have been up close and personal in so many situations where brothers and sisters in Christ have fallen out. I saw how easily quarrels and disputes could arise between fundamentally good and well-intentioned people, often not through malice but through miscommunication and vastly different expectations.

The surface level answer to whether a Christian business owner should sue is “NO!”. I Googled everything I could but the online articles didn’t seem to address the reality that directors, even if they are Christians, have fiduciary duties to act in the best of interests of the company as they are stewards for others not just their own resources. This introduces nuance and tension and many other questions.

In this article I attempt to share some of my thoughts. It is in no way to be considered the ‘right answer’ and would welcome the opportunity to revise this down the track if anyone can shed more light on this tension. This article does not seek to offer a definitive rule. Instead, it explores the ethical terrain Christians must navigate when faith, legal obligation, and business reality collide. Get in touch!

Here are Paul’s challenging words:

“If any of you has a dispute with another, do you dare to take it before the ungodly for judgment instead of before the Lord’s people?” (1 Corinthians 6:1)

At first reading, the conclusion seems obvious: Christians should not take other Christians to court. Yet for those operating in the modern UK business and charity landscape—directors, partners, trustees, founders—the issue is rarely straightforward. Commercial life introduces layers of responsibility, power, and consequence that create genuine moral tension rather than easy answers.

What Was Paul Really Condemning in 1 Corinthians 6?

Paul’s rebuke in 1 Corinthians 6 is sharp, but it is not abstract. He is addressing a specific practice in a particular historical setting: believers taking one another before pagan courts in a highly status-conscious society.

To understand the force of his argument, it helps to picture what those courts were actually like.

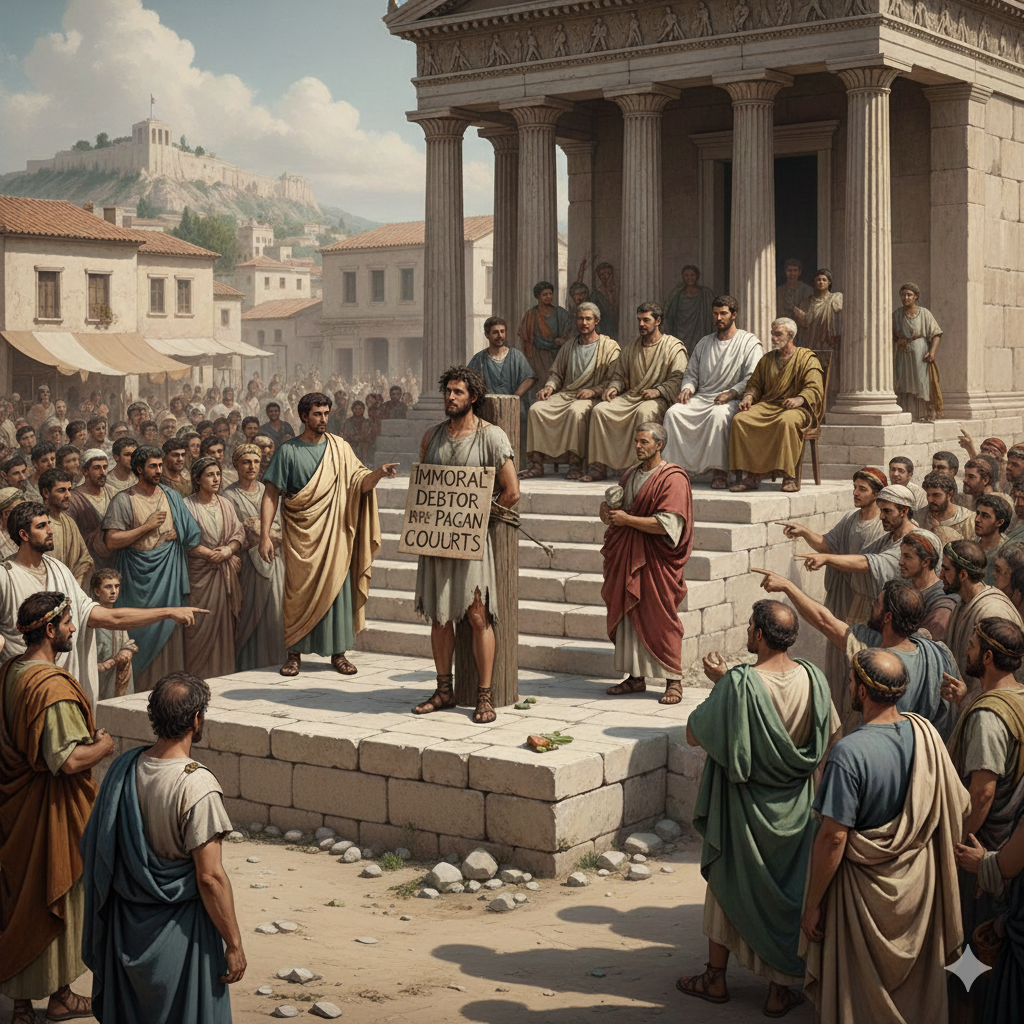

The Pagan Courts of Corinth: Power, Status, and Public Shame

First-century Corinth was a thriving commercial city. Trade, shipping, property, and contracts mattered enormously, and disputes were common. Yet the legal system available to ordinary people bore little resemblance to modern English law.

Roman courts in cities like Corinth were public, political, and deeply unequal. Cases were often heard in open civic spaces. Magistrates were drawn from the social elite, and outcomes were shaped as much by status, patronage, rhetoric, and influence as by evidence or principle. Those with wealth, connections, or social standing tended to prevail (Garnsey, 1970).

Pagan Courts of Corinth

Legal action was also commonly used as a tool of social dominance. To sue someone was to shame them publicly, assert superiority, and reinforce one’s place in the social hierarchy. Even relatively minor disputes—over debts, contracts, or commercial arrangements—were sometimes pursued precisely because the process itself rewarded the powerful.

Against this backdrop, Paul’s outrage becomes clearer. His shock appears directed at believers dragging one another into a system designed to reward the powerful and shame the weak, rather than resolving matters within the Christian community shaped by humility and love.

What Kind of Disputes Was Paul Referring To?

The disputes Paul has in mind were almost certainly civil and commercial rather than criminal. The language he uses points to disagreements over money, property, debts, or business dealings. Major commentators agree that Paul is not addressing serious crimes requiring public prosecution, but rather financial or contractual disputes between believers (Fee, 1987; Thiselton, 2000).

Some scholars suggest these were relatively minor cases—the ancient equivalent of what we might today call small claims—yet pursued aggressively because of the honour to be gained by winning publicly. Others note the bustling marketplace economy of Corinth, where such disputes would have been commonplace.

What seems unlikely is that Paul was condemning every conceivable form of legal adjudication. Rather, he was confronting a particular moral failure: Christians importing the values of a competitive, status-driven culture into the life of the church.

What Paul Is — and Is Not — Condemning

This historical context helps sharpen the ethical focus of the passage.

Paul is not condemning all forms of structured adjudication. He is condemning a culture of adversarial self-assertion, where believers imitate the world’s methods of winning rather than embodying Christ’s way of reconciliation.

The issue is not simply where disputes are resolved, but how and why. Paul’s concern is with rivalry, pride, public vindication, and the desire to prevail over another believer.

Seen this way, the question for modern Christians is not simply:

“Should we ever take legal action?”

but rather:

• Are we acting out of love or out of rivalry?

• Are we seeking justice or public vindication?

• Are we protecting the vulnerable or asserting our rights at their expense?

These questions probe motives as much as mechanisms.

When Disputes Are Not Merely Personal

The challenge becomes more acute when disputes are not simply between two individuals.

Many Christians today act as directors of companies, partners in firms, or trustees of charities. Under UK law, these roles carry fiduciary duties. Directors must act in good faith in the best interests of the company. Trustees must safeguard assets for beneficiaries. These are not optional expressions of personal virtue; they are legally enforceable responsibilities to others.

In such cases, choosing simply to “absorb the loss” may not be an act of Christian grace at all. It may constitute a failure of stewardship—particularly where inaction causes harm to employees, donors, shareholders, or beneficiaries who have entrusted resources to Christian leadership.

Paradoxically, an attempt to be personally virtuous may become professionally negligent.

Parties weaponising 1 Corinthians 6 to avoid accountability

A further pastoral difficulty arises when one party disregards clear contractual or legal obligations, apparently calculating that their Christian counterpart will feel unable to respond robustly.

Appeals to grace, forgiveness, or “not taking a brother to court” can—sometimes unintentionally, sometimes cynically—be used to avoid accountability. When this happens, the harm is rarely abstract. Cashflow suffers. Charities lose funding. Staff and stakeholders bear the cost. In some cases I have seen investors pull back from investing altogether.

Christian ethics has always placed strong emphasis on truthfulness and faithfulness to one’s word. To exploit another’s conscience for commercial advantage sits uneasily with any serious account of discipleship. Grace is not permissiveness, and forgiveness does not eliminate responsibility.

Modern UK Law and Moral Complexity

It is also important to acknowledge that business disputes are rarely clear-cut.

Under English law, disagreements often hinge on:

• Competing interpretations of contracts

• Disputed factual accounts

• Complex company or charity law obligations

Well-intentioned Christians may honestly disagree about what justice requires. The UK legal system itself recognises this complexity, which is why mediation, arbitration, and negotiated settlement are strongly encouraged.

This should foster humility. Legal action between Christians should never be undertaken lightly, vindictively, or triumphantly. Yet nor should it be ruled out automatically, as though any engagement with law were inherently unfaithful.

The danger Paul identifies lies not in structure, but in spirit.

Mediation, Arbitration, and Christian Wisdom

One constructive response is to plan for dispute before it arises. Many Christian business leaders advocate:

• Mediation clauses in commercial contracts

• Christian conciliation or arbitration

• Independent mediators who understand both law and faith

Such approaches reflect Paul’s desire for disputes to be handled by the “wise” rather than through public, adversarial spectacle. They also align closely with the UK legal system’s preference for alternative dispute resolution.

These mechanisms do not guarantee agreement, but they create space for accountability without humiliation, and justice without unnecessary damage.

Personal Sacrifice and Corporate Responsibility

A final distinction remains crucial.

A Christian leader may choose to absorb personal cost for the sake of peace. But they are not free to give away assets that belong to others—shareholders, members, donors, or beneficiaries—simply to avoid conflict.

Faithfulness may sometimes require difficult conversations, formal processes, or even legal enforcement. When it does, such action should be undertaken with restraint, prayer, and a genuine desire for restoration rather than victory.

Living Faithfully with Tension

1 Corinthians 6 refuses to let Christians become comfortable with conflict. It challenges our instinct to defend ourselves at all costs. Yet it sits alongside a broader biblical concern for justice, stewardship, and the protection of the vulnerable.

For Christian entrepreneurs in the UK, the task is not to collapse this tension into simple rules, but to inhabit it wisely—resisting both naïve idealism and cynical pragmatism.

Sometimes faithfulness will look like choosing costly peace. At other times, it may require naming wrongdoing clearly and acting to prevent further harm. In all cases, the way Christians handle business disputes may speak as loudly as any statement of belief.

The question is not simply whether Christians ever take legal action—but whether, in all things, they reflect the character of Christ.

Further Reading

Fee, G.D. (1987) The First Epistle to the Corinthians. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

Garnsey, P. (1970) Social Status and Legal Privilege in the Roman Empire. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Thiselton, A.C. (2000) The First Epistle to the Corinthians: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.